|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Rising inequality - a major global challenge As the issue of rising global inequality highlighted by Thomas Piketty's bestseller comes to the fore, Mah-Hui Lim argues that such inequality threatens not only social and political stability, but also, in the long run, economic growth and financial stability. THE issue of inequality, which was shunted aside amidst rapid growth over the last few decades, has resurfaced with a vengeance, particularly after the latest global financial crisis. A recent report on inequality by the development charity Oxfam, presented at the 2015 World Economic Forum in Davos, hit the headlines. It shows that the top 1% of the world's population own 48% of the world's wealth, while the bottom 80% own only 5.5%; and this gap is likely to widen. It has also been reported that inequality has reached its highest level in the US since such records were kept over 100 years ago. This issue not only afflicts the poor but also worries the rich. Li Ka-shing, Asia's richest man, said publicly that he is kept awake at night over rising inequality, and Janet Yellen, the US Federal Reserve Chairperson, has raised this issue in one of her recent speeches, inviting the ire of Republican Party leaders. It is widely believed that growth based on free markets is what matters, and that the benefits of growth will automatically trickle down to the rest of society. This trickle-down theory of growth is now called into question, however, by one of the global mega-trends occurring over the last four decades, i.e., economic inequality has been rising in most countries in the world despite rapid economic growth. This is particularly true in Asia, which has witnessed such phenomenal growth. A 2012 report by the Asian Development Bank showed that 13 of 36 Asian economies had a Gini index of 0.4 and above, and 11 economies covering 82% of Asia's population experienced worsening inequality. Why should we worry about rising inequality? It is imperative to address this issue because rising inequality threatens not only social and political stability but also economic growth and financial stability. Measuring inequality Economists often use the Gini index to measure the degree of economic inequality in a country. The index covers a scale of 1 to 0; 1 refers to absolute inequality and 0 to absolute equality. Countries with a Gini index of 0.4 and above are regarded as highly unequal. In Asia, these include Singapore (0.47), China (0.51), Malaysia (0.46), the Philippines (0.43), India (0.40), Pakistan (0.68, estimated by some sources) and many others. In many cases this index is rising. Among the rich countries, the US, with an index of 0.46, stands among the most unequal. A more intuitive measure of inequality is the percentage of income or wealth owned by the top 1% or 10% of households in a country versus, say, the bottom 50%. Thomas Piketty's book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which uses this approach, is making waves internationally. He and his colleagues have collected such data spanning centuries and different countries. For example, Figure 1 shows that the top 1% of households in the US account for over 20% of total income in the period prior to the Great Depression of 1929 and the Great Recession of 2008.

A more important, but less used, measure of economic inequality is functional income distribution, i.e., the percentage of a country's gross domestic product (GDP) going to labour (wages and benefits) compared to capital (profits, rents, interest, dividends). An ILO (2011: 55) study shows that since the early 1990s, three-quarters of the 69 countries for which functional income distribution data are available experienced a declining labour share of income. This is happening in both developed and less developed countries. Figures 2 and 3 show the declining labour share in these countries. In Asia the labour share declined by almost 20% since 1994.

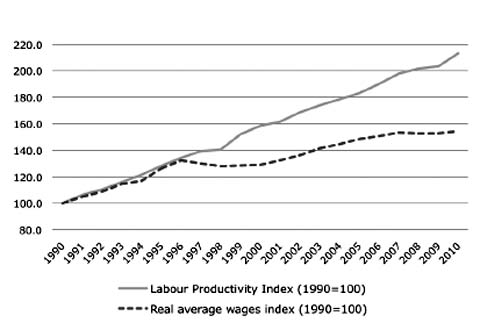

Why is inequality worsening? Technological change is often cited as the major driver of income inequality; technology favours workers with higher levels of education and skills, and hence the income gap between skilled and less skilled labour widens. However, beyond this, there are other important factors to consider. Chief among these are events related to forces of globalisation, financialisation and international relocation of production - all of which weakened the bargaining power of labour in the less developed as well as the developed countries. With the collapse of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1971, the international monetary system went off the US dollar-gold standard, and from fixed to floating exchange rates. Financial liberalisation ushered in the era of free international capital flows. Together with changes in technology and business organisation, this enables multinational corporations to freely invest and relocate production anywhere in the world, pitting one country against another. The entrance of billions of unemployed or underemployed workers in peripheral countries like China, India and Southeast Asia into the global workforce facilitated the global arbitrage of labour, i.e., capital is now able to move freely in search of countries with the lowest costs. Many Asian countries competed, and still do, for foreign investments by repressing unions and wages, which puts a brake on wage demands in both the poor and richer countries. This weakened labour's bargaining power globally and is reflected in the rise of temporary and contract labour, and stagnating or declining wage income. As a result of these forces, wage growth did not keep up with the rise in labour productivity in many countries. This divergence between productivity growth and wage growth is illustrated in Figures 4, 5 and 6 for the US, China and South Korea respectively. In other words, capital has been creaming off most of the gains from productivity growth since the 1980s.

Impact of rising inequality The implications and consequences of rising economic inequality are multi-faceted. Firstly, social and political democracy is undermined when there is extreme inequality. The Asian Development Bank did a survey of over 500 national policymakers in Asia in 2012 and found that 95% of respondents thought it important to have policies to prevent a further rise in inequality to maintain political stability and economic growth. Alan Greenspan, former Chair of the US Federal Reserve, put it succinctly when he said in 2007 that while he did not understand why there was a long-term divergence between productivity and wage growth, as shown in Figure 4, he was worried that if the trend continued unabated, political democracy would be threatened. The recent Occupy movements in the US and other parts of the world that followed in the wake of the global financial and economic crisis speak to this risk. Secondly, beyond political and social instability, rising inequality is also not good for financial stability and economic growth. A recent International Monetary Fund study shows that inequality is not good for long-term growth. While it is possible to produce growth spells irrespective of inequality, the study finds that income distribution is one of the most robust predictors of sustained growth. Furthermore, extreme inequality misallocates human resources and is often associated with weak institutions and governance. Thirdly, inequality is related to financial instability [for a detailed analysis, see Lim and Lim (2010), and Lim and Khor (2011)]. The recent global financial crisis is not simply the result of greedy bankers, poor corporate governance and inadequate banking regulations, although these problems must be addressed. There are even more serious underlying structural causes to the crisis, one of which is rising inequality. It is widely recognised that global trade imbalances contributed to the crisis, i.e., China and other Asian countries have enormous trade surpluses which funded the huge trade deficit in the US. But behind this trade imbalance is wealth and income imbalance. China's declining labour share of GDP is reflected in its drastic drop in personal consumption (from over 50% to 35% of GDP in the last four decades) and the concomitant rise in its savings rate from about 30% to over 50% of GDP. This excess of savings over investment, which is the current account surplus, is recycled through the international financial system and funded US consumption, which reached 72% of GDP in 2007. How was it possible for consumption to rise in the US when real wages there were stagnating or even declining? Essentially consumption was supported by debt rather than income. Between 1960 and 2006, US GDP rose 26 times but household debt rose 64 times, reaching close to 100% of GDP in 2006. Much of this was mortgage debt that eventually imploded in 2007. Wages are not simply a cost factor in economic growth; they are also an important factor driving aggregate demand. If wages are repressed, then aggregate demand and economic growth are negatively affected unless there are compensating mechanisms to prop up aggregate demand. Debt is one such mechanism. However, there are risks and limits to pumping up consumption through debt, as amply demonstrated in the US financial crisis. A number of Asian countries are exhibiting similar tendencies. In South Korea and Malaysia, where the wage share is declining as wages fall behind productivity growth, household consumption and debt have been climbing to dangerous levels. The ratio of household debt to GDP was 89% in South Korea in 2010 and 87% in Malaysia in 2013; even more alarming, the ratio of household debt to disposable income was 164% in South Korea and 140% in Malaysia (2012). The lesson from the US debt-driven consumption and financial crisis because of rising inequality and declining wage share should be instructive to these countries. What policy responses? Given the significant risks of unchecked rising inequality, what can or should be done? It is possible to address this issue from an ex-ante and/or ex-post manner in terms of income distribution. To tackle it in an ex-ante manner, it is clear that real wages must rise in tandem with increases in productivity to support healthy aggregate demand growth. A prolonged divergence of the two trends, with wages either lagging behind productivity increases or overshooting productivity increases, is economically and politically destabilising. Addressing it in an ex-post manner, state policies can reduce inequality through more progressive fiscal policies - by increasing capital gains tax, reintroducing inheritance tax, more progressive taxation and provision of better social services and safety nets. In the past three decades, government policies in many countries have favoured the wealthy with reductions in income and capital gains taxes, and cutbacks in social spending and safety nets. Essentially state policies have exacerbated inequality. The pendulum of inequality has veered too far over the past few decades and something must be done to bring it to balance lest we face more serious crises. Mah-Hui Lim was formerly a post-doctoral fellow at Duke University and Assistant Professor at Temple University in the US, and an international banker. References ILO (International Labour Organisa- tion), 2011. World of Work Report 2011. Geneva. ILO, 2013. Global Wage Report 2012-13. Geneva. Lim, Mah-Hui, 2014. 'Globalization, Export-Led Growth and Inequality: The East Asian Story'. Research Paper 57, South Centre, Geneva. Lim, Mah-Hui and Khor Hoe Ee, 2011. 'From Marx to Morgan Stanley: Inequality and Financial Crisis'. Development and Change, Vol. 42, No. 1, January, pp. 209-227. Lim, Mah-Hui and Lim Chin, 2010. Nowhere to Hide: The Great Financial Crisis and Challenges for Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore. Piketty, Thomas, 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. *Third World Resurgence No. 293/294, January/February 2015, pp 4-7 |

||

|

|

||