|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Looking in a gift horse's mouth The

persistence of food crises and food price volatility has spawned some

false solutions. The most notable of these is the 'New Green Revolution

for THE

largest 'private charitable operation' in the world today is the Bill

and Melinda Gates Foundation, headquartered in our hometown, The

slogan of The original 'Green Revolution' several decades ago was a term used to describe high-technology agricultural development. As described in the Britannica Concise Encyclopedia: 'Great

increase in production of food grains (especially wheat and rice) that

resulted in large part from the introduction into developing countries

of new, high-yielding [seed] varieties, beginning in the mid-20th century.

Its early dramatic successes were in Old vs. new The vision of the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations, who supported the original Green Revolution, to solve hunger focused on the improvement of crop yields; they simply equated hunger to poor food production and relied on an industrial agricultural model, using high-yielding seed varieties (HYVs), chemical fertilisers, pesticides, mechanisation and mono-cropping. In the early stages of the Green Revolution the new technologies proved to be capital-intensive, which was a barrier preventing many small farmers' participation. The 'remedy' for this was a package that included access to credit, training, and smaller packages of inputs. Still, many farmers were unable to sustain themselves in the competitive and capital-intensive environment created by that Green Revolution. The technologies used in the original Green Revolution resulted in several major negative consequences (see box). Despite

these failures, Bill Gates, in a speech given at the 2009 World Food

Prize Symposium held in There is little reason, therefore, to expect that a 'new' Green Revolution will reduce (much less eliminate) global hunger. Organisational shell game While

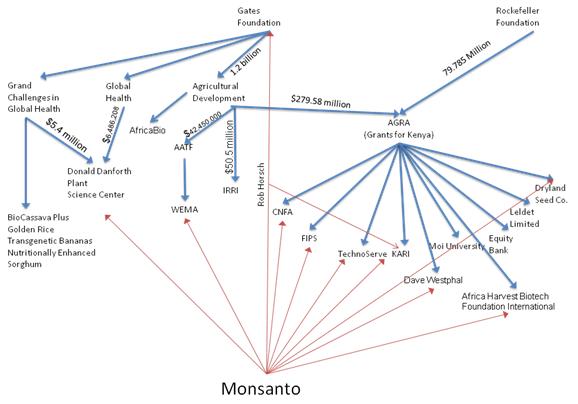

the Gates Foundation works hard to separate itself from The

web of inter-relations between Gates and * 'Our mission is not to advocate for or against the use of genetic engineering.' *

' These statements, we have found, are doublespeak or outright falsities, inconsistent with the claim on the website of the parent Gates Foundation that 'we demand ethical behavior of ourselves'.

Following

the money from the Gates Foundation and * Not all of the work that the Gates Foundation is doing around GMOs is obvious; research into genetically engineered sorghum, bananas, rice, and cassava is being funded through its separate initiative, Grand Challenges in Global Health, under claims of adding nutrition. * In addition, the Gates Foundation is also funding organisations that are known for influencing African government policies to allow for the use of GMOs, such as AfricaBio and Africa Harvest Biotech. *

In a 'revolving door' situation, individuals move among the organisations

in the diagram, making the parts function in a coordinated and mutually

reinforcing fashion. One of AfricaBio's board members, Jennifer Thomson,

is also Chair of the African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF),

which is partnered with Monsanto to work on a project called Water Efficient

Maize for Africa (WEMA) - funded by the Gates Foundation. In another

example, Florence Wambugu founded Thus is woven the web. When

AGRA president, Dr Namanga Ngongi, was asked in Global Health magazine

about AGRA's 'dalliance' with Monsanto resulting in 'genetically modified

organisms being heaped onto unsuspecting farmers,' he claimed 'If anything,

AGRA is counteracting Monsanto as it strives towards supporting the

capacity of countries to produce seed using their own natural plant

genetic material.' This response glosses over Further,

Ngongi ignores that Why

is Monsanto's

history evidences no concern whatsoever for reducing rural poverty or

increasing food production and nutrition, the stated goals of the Gates

Foundation/AGRA efforts. In fact, Monsanto has already negatively impacted

agriculture in African countries. For example, in When

we track the funds from the Gates Foundation through Why

shouldn't New technologies do not benefit everyone - some people lose while others gain, some gain a little and others gain a lot. Despite the dominant ideology that technologies are value-neutral, they actually are imbued with specific human intentions, because they are purposeful interventions into the natural progression of activities. (By definition, they are not acts of God or of Nature.) In class-stratified societies, new technologies embody the values, perspectives, purposes and political/economic objectives of powerful social groups. Because of their size, scale, requirements for capital investment and specialised knowledge, modern technologies are powerful interventions into the natural order. They tend to be mechanisms by which already powerful groups manifest, extend, and further consolidate their powers. Thus, the prevailing view that a technology is only troublesome when it is 'abused' (rather than perhaps having inherent negative characteristics) is a form of social mystification, to deflect criticism from the technical activities of the powerful. That

the Gates Foundation, a rich and powerful social actor, has embraced

genetic engineering technologies for its ventures into So, for example, the Foundation has given money to develop drought-tolerant maize. But, as Jos Ngonyo, of the Kenya Biodiversity Coalition, has pointed out, 'we already have water-efficient maize. It does really well. It's called katumani. It's grown in dry areas and takes only three months to grow before people have food to eat.' High tech, however, is 'where the money is'. Thus, the overall effect is to shift control of the food supply from local people to international entities. Gates'

personal and business life certainly reflects a mode of technological

triumphalism - that one can achieve omniscience and perfection through

high-tech social interventions. For agriculture in Genetically

engineered (GE) crops and foods fall squarely within this model, and

thus are not really amenable to democratic control by Africans, nor

are they environmentally or socially 'sustainable'. High-chemical inputs

and mechanisation also fall within this model, but their negative social

and environmental impacts are well known. The consequences of the Gates

Foundation and Genetic engineering technologies are based on a reductionist view of an organism's genome, simplifying a complicated dynamic reality into a static LEGO-like construction. Yet, the composition of a genome is not determinative of its functions (since, for example, the cells in human eyes are the same as those in the pancreas, yet the eyeball does not make insulin). The location of the various components in the genome, their internal interactions, and the control and moderation by a huge number of proteins circulating in the organism actually determine a cell's functioning. As a result, scientists do not know all the outcomes when they introduce a new piece of genetic material or rearrange what Nature has already provided. Despite the real and possibly substantial likelihood of health risks to humans and the environment posed by the production and consumption of GE foods, almost no research is being funded to assess such risks, since it would not be in the interests of industry nor government to do so (since they believe that GE will be the next big economic 'driver'). Although a few independent scientists and technical panels have called for an end to this approach of 'don't look/don't find', there is essentially no adequate regulatory oversight being performed. When pressed to expand such monitoring and regulation, those behind the technology claim that concerns are groundless; yet no evidence of harm is not the same as evidence of no harm. And the few inconvenient danger signals which have turned up are explained away, 'pooh-poohed', and scientists associated with them have lost research funds and been vilified (such as Arpad Pusztai, author of over 300 peer-reviewed articles, who was dismissed from his position at Rowett Research Institute in Scotland in 1998 when he discovered cell changes in rats fed GE potatoes - despite this research being published in the prestigious Lancet medical journal). So it is not surprising, for example, that a statement made by participants from 25 African countries (and 10 from other continents) at a conference at Ny‚l‚ni centre in Selengue, Mali, November-December 2007 declared, 'The push for a "new green revolution in Africa", GMOs and other initiatives of the biotech, chemical fertiliser and seed companies have to be stopped.' The main risks of GE crops There are many Africans who have articulated the risks presented by GE crops. These can be seen to fall into a number of categories, although they are in reality all intertwined. * Risks to human health. Although the biotech industry claims that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has thoroughly evaluated GE foods and found them safe, this is not so. In 1992, the industry/government group called the Council on Competitiveness, headed by US Vice-President Dan Quayle, announced that the FDA would not specially regulate GE foods because they were 'substantially equivalent' to unmodified varieties (of course, the industry then goes across the street to the patent office and argues that they are completely novel and not like anything else). Internal FDA documents obtained in the course of a lawsuit reveal that agency scientists vigorously opposed this logic of equivalency, warning that GE foods might create toxins, allergies, nutritional problems and even new diseases that might be difficult to identify. Only about two dozen published peer-reviewed studies have subsequently appeared; many of these appear to have been rigged, were selective in the evidence pursued, were sponsored by industry, or suffered from poor research design. Clearly the public interest would require that a great deal of health research be conducted. * Genetic contamination of African biodiversity by GE crops. The

main food crops in Africa are often indigenous and thus engineered elements

can alter the genetic make-up of native plants or disturb the ecological

balance in other ways (such as by creating 'superweeds' which are resistant

to herbicides). Over 165 examples of such contamination occurred in

2005-07 alone - by pollen flow, the careless escape of GE seeds, etc.

- resulting in hundreds of millions of dollars in damages. Although

millions of dollars were paid in damages to other industry sectors,

these were largely obtained by corporations powerful enough to force

out-of-court settlements. African farmers would not have the financial

capability to recover for damages to their crops by suing agribusiness

giants such as Monsanto; in fact, even more affluent farmers in This

sort of contamination appears to be a conscious strategy by the industry

and the * Other impacts on biodiversity. Some studies have indicated that benign or beneficial insects (butterflies, aquatic species) can be adversely affected by eating the pollen or other parts of GE plants, with unknown consequences. At the other extreme, constant exposure to insecticidal and herbicidal genetic material can lead to Darwinian development of resistance in pest species. * The economic ramifications of GE crops are enormous. GMOs are protected by patent monopolies, increasingly putting the food supply under the control of a small number of multinational firms. Should GE species, still largely products of nature, even be patentable? Most of the information on GMOs (admittedly not a large data pool to begin with) is unavailable for public scrutiny, under claims of 'confidential business information'. In addition, the agencies which might exercise some oversight on biotechnology have experienced a 'revolving door' in which officials of agriculture biotech firms such as Monsanto are appointed to public positions, set lenient policies, and then return to their lucrative corporate perches. The 'revolving door' now opens up to the philanthropic world as well; Rob Horsch is a case in point. The Precautionary Principle Most

African countries are among the 157 Parties to the UN's Cartagena Protocol

on Biosafety which, among other things, establishes the policy of using

the Precautionary Principle in regard to risk assessment - in other

words, 'look before you leap' and don't commercialise any GMO that has

not been fully assessed for risks. The US, Finally,

Africans are aware that the UN food and health agencies and the World

Bank sponsored a major 'International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge,

Science and Technology for Development' (IAASTD) which issued its final

report in 'A problem-oriented approach to biotechnology R&D [research and development] would focus investment on local priorities identified through participatory and transparent processes, and favor multifunctional solutions to local problems. These processes require new kinds of support for the public to critically engage in assessments of the technical, social, political, cultural, gender, legal, environmental and economic impacts of modern biotechnology. Biotechnologies should be used to maintain local expertise and germplasm so that the capacity for further research resides within the local community. Such R&D would put much needed emphasis onto participatory breeding projects and agroecology.' Notably,

The Gates Foundation is offering its agricultural aid to Africans along the lines advocated by these three rogue states instead of following the approaches subscribed to by the overwhelming majority of Africans. On its website and elsewhere, the Foundation knows how to 'talk the talk': 'Guiding Principle #9: We must be humble and mindful in our actions and words. We seek and heed the counsel of outside voices. Guiding Principle #10: We treat our grantees as valued partners, and we treat the ultimate beneficiaries of our work with respect. Guiding Principle #11: Delivering results with the resources we have been given is of the utmost importance - and we seek and share information about those results.' But it doesn't seem to 'walk the walk', as we have seen. We may recall the teaching of Dr Martin Luther King on 4 April 1967, exactly one year before he was killed: 'True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.' Philip

Bereano is Professor Emeritus at the

They are founding members of

*Third World Resurgence No. 240/241, August-September 2010, pp 44-48 |

||

|

|

||